Corn Hybrid

Mixing

Recent headlines and discussions have

pondered mixing seed from two different corn hybrids to increase yield. The

idea of blending seeds from different varieties or hybrids has been around

for quite some time. The theory is that two hybrids planted together in the

same field might be able to produce a yield superior to what the varieties

would produce on their own. This theory is based on two main ideas; first

is that two hybrids may use the resources of light, fertility or water in

patterns that complement each other. Another way of understanding this concept

is to imagine the possibility that two plants from different hybrids are less

competitive with each other than two plants from the same hybrid. The second

idea and the one being advanced most recently is based on the potential to

stimulate hybrid vigour in the seed of a commercial corn crop. When the pollen

of hybrid A pollinates the ear of hybrid B there is the potential for this

vigour to cause kernel size to be greater than if hybrid B received its own

pollen. Several key studies will shed some light on the practicality of these

ideas.

Guelph Work

Corn hybrid blending was

examined in 1978 and 1979 in work done at the University of Guelph by Gary

Hoekstra (now at Kemptville College, University of Guelph). He examined a

number of different corn hybrids under different populations, while blending

the hybrids in mixtures of various proportion. His experiments focused particularly

on the competition effects between hybrids in trying to arrive at mixtures

that would use the available resources more efficiently. The results from

Hoeskstra’s research showed hybrid mixtures never outyielded the highest

yielding hybrid used in the mixture when it was planted in a pure stand.

Minnesota

Trials

The work that has gained

the most attention on this issue lately comes from Minnesota, from Dr. Mark

Westgate (currently at Iowa State University). He focused on the effects that

hybrid mixing (and the resultant cross pollinating) could have on seed size

and grain yield. This study compared hybrid mixing on a large number of on-farm

sites in 1997. Farm co-operators were asked to set up trials comparing two

hybrids planted in an every-other-row pattern. The yields obtained from this

mixed planting were then compared to yields from neighbouring plots where

hybrids A and B were planted in pure stands. They reported about a four-bushel

average gain in yield from mixing hybrids as long as the hybrids were from

different seed companies; when hybrids came from the same company there was

no yield advantage to the mixture. This suggests the cross-pollinating boost

to seed size or yield is greater from two hybrids that have different parentage

and that this would be more likely when hybrids came from different companies.

It should be pointed out, however, that all seed companies do not exclusively

use their own parent material, so a grower would have no way of knowing whether

the parentage of hybrid A from one company could indeed be similar (or dissimilar)

to hybrid B he selected from another company. Dr. Lori Carrigan, Pioneer Hi-Bred

Ltd. has suggested another of the key reasons mixtures generally don’t

yield more is that 50-75 per cent of the pollen that an ear receives is from

its own tassel, eliminating any cross pollinating boost to seed size.

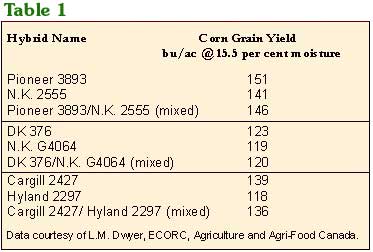

1998 in Ottawa

This past season Dr. Lianne

Dwyer of Agriculture and Agri-food Canada in Ottawa set out to compare three

different sets of corn hybrid mixtures. The hybrid pairs were selected based

on having similar maturities and similar yield potentials. Unlike the work

in Minnesota these hybrids were physically mixed together in equal portions

before being placed into the planter unit hopper. One would have expected

this sort of mixing to increase the percentage of cross-pollinating between

hybrids that occurred relative to an alternate row mixture. Table 1 outlines

the corn hybrids and yield results from this study and illustrates that the

hybrid mixtures always produced a yield somewhere intermediate to the low

and high yields obtained from planting the two hybrids in pure stands. Again

there was no evidence to suggest that the mixture could outyield the best

hybrid when planted by itself.

Bottom Line

The evidence to support hybrid

mixing as a practical approach to increasing corn yields is thin. The biggest

negative is that it would take a fair bit of time and work to finally arrive

at the two hybrids that would combine to consistently produce a yield advantage.

The day you arrive at that mixture is the day five new hybrids appear on the

scene with yield potential or quality traits that surpass anything in your

mix.